Everything You Need To Know About MSG

That incredible bucket of movie theater popcorn. A fast food chicken sandwich. An order of beef and broccoli at the neighborhood Chinese restaurant. Biting into any of these taste-rich foods may make you believe that the taste of food can be an almost otherworldly experience. However, that nearly spiritual experience you may have had simply reflects the presence of one key ingredient.

We are talking about monosodium glutamate or MSG. Over the years, this flavor-bolstering bit of fairy dust has taken a bad rap, being blamed for various conditions, like heart palpitations, headaches, and a case of the sleepies. Although many have come around in their thinking about MSG, the beliefs about it still vary widely. Some consider it an important ingredient that may or may not be second only to salt and curry spice in the spice world hierarchy. Others think it's an abomination and, therefore, should be banished to the far corners of the globe just to be safe.

The truth about monosodium glutamate actually lies somewhere in the middle of all these beliefs and is worth looking into. So, let's unravel the truth from the false about MSG and try to figure out where these misconceptions come from.

MSG occurs naturally in many foods

If we could just ban all MSG, life would be better, right? Well, that probably depends, given the fact that MSG occurs naturally in almost all foods. You read correctly. Monosodium glutamate occurs in foods we eat on the regular. In fact, you'll find it in high-protein foods, like meat, cheese, and fish. In addition, carrots, tomatoes, beets, corn, and onions are sources, too. Other sources include soy, yeast extract, and hydrolyzed yeast.

Basically, we're saying that MSG is pretty much everywhere. You can even find monosodium glutamate in breast milk. A more helpful question for the informed eater might be what MSG occurs naturally in the foods we're eating and what MSG comes from a food manufacturer and has later been added to our food. Incidentally, the FDA does not require MSG to be listed in the ingredients if it occurs naturally in a food, but it must be listed if it's added separately.

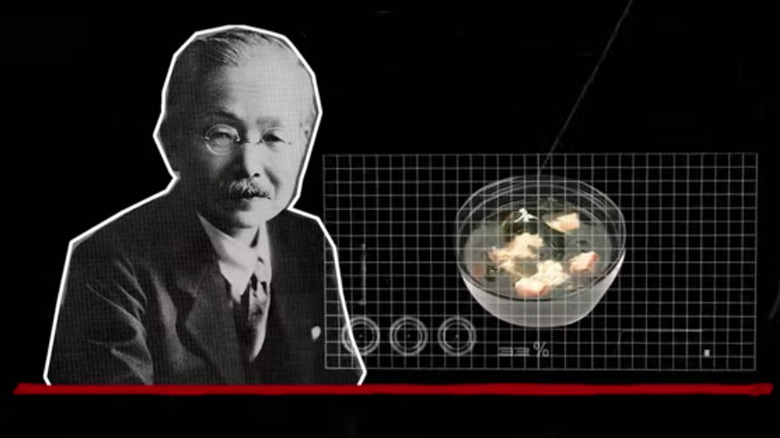

Kikunae Ikeda is credited with developing it

Dr. Kikunae Ikeda, a Japanese chemist, was the first to extract monosodium glutamate, and while his name may not be ubiquitous among most consumers, the raw materials he used to create the MSG are: seaweed. Near the turn of the 20th century, a happenstance question to his wife about what made her dashi soup broth taste so good put the scientist on a taste odyssey that changed cuisine forever. Following that conversation, Ikeda gathered some kombu seaweed, put it in his scientist's beaker, and extracted glutamate from the mix. Ikeda christened the taste of his invention umami. If you've ever eaten a bowl of ramen noodle soup, then you are familiar with umami. It's the savory taste in Asian recipes. Well, any recipes that have a savory taste, for that matter.

Ikeda's first experiments netted him 30 grams of MSG. It was he who was responsible for creating the crystalized form of MSG. His invention, which resembles table sugar or salt, caught on. For many home cooks in Japan, glutamate practically became more prized than their best knife sets. For a time, it got so much love from the umami-loving public that a symposium was held by U.S. soldiers after World War II. They wanted to add MSG to field rations to make them taste better. For them, better-tasting food equaled higher morale among the enlisted men.

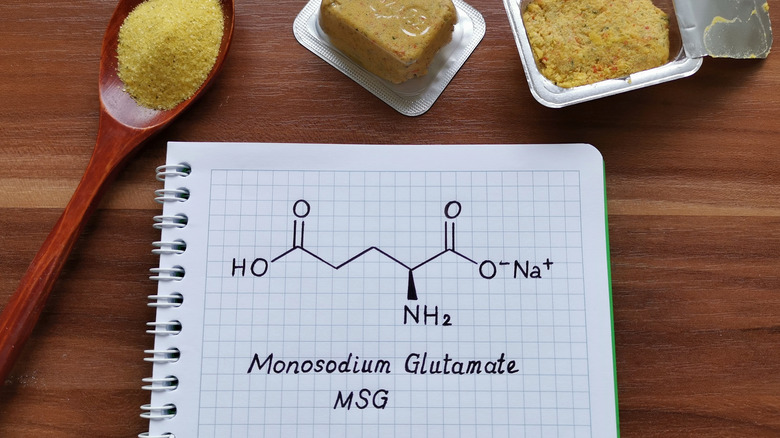

MSG is a non-essential amino acid

L-glutamic acid contains a type of salt, and that salt is known to us as glutamate or MSG. However, it's not as salty as, say, table salt. Table salt has two-thirds more sodium than MSG. As it turns out, the addition of monosodium glutamate to a recipe can reduce the need for table salt by 40% without killing the flavor of the dish. Kikunae Ikeda, the chemist who gave the culinary world the salt-shaker form of MSG, discovered that C5H9NO4, MSG's chemical makeup, was the same as the amino acid glutamic acid. This is a non-essential amino acid that, far from being harmful to most humans, is created naturally inside the human body's own chemistry factory.

On a related note, you may recall that there are nine amino acids, the so-called essential amino acids, like lysine and tryptophan, that the body cannot produce on its own. You must get those amino acids by eating foods that contain those amino acids. MSG, as a non-essential amino acid, is produced by the body on its own. As it turns out, many of the foods we eat — cheese, meats, and poultry — give us both essential and non-essential amino acids, including MSG.

You'll find it under many names

We have a question for you. Would MSG by any other name still taste as savory? And, while being the foodie equivalent of a Shakespearean poem seems a bit silly, the question deserves an answer. As it turns out, MSG goes by many names on food labels. Among them are names like glutamate, sodium caseinate, yeast nutrient, autolyzed yeast (or autolyzed yeast protein), pectin, soy isolate, whey protein isolate, hydrolyzed corn, vegetable extract, and Ajinomoto, which is, incidentally, what Dr. Kikunae Ikeda named his company after discovering how to make MSG in the lab.

It's also worth noting that any food label containing words like protein fortified, hydrolyzed, fermented, and ultra-pasteurized will have glutamate in them, which means the hydrolyzed corn listed above is a big MSG reveal if you know what to look for. Additionally, you can look for ingredients like malt extract, citric acid, protease, seasonings, and soy sauce. Those ingredients contain glutamic acid, too.

MSG producers use a fermentation process

To make his now-famous invention, Dr. Kikunae Ikeda boiled down a concoction of seaweed broth, more or less, until it evaporated. The process of evaporation left behind the crystals that became the first MSG. However, the revolutionary process that eventually earned the good scientist a patent isn't how MSG is made today. Instead, companies that manufacture monosodium glutamate use a fermentation process to create the product. Ingredients like molasses, sugar beets, or sugar cane get tossed into a vat and fermented. Once the bacteria in the vats of soon-to-be-MSG are done doing their thing, sodium hydroxide neutralizes the process, and MSG in all its powdery goodness is the result.

Incidentally, it's the addition of sodium to glutamate in MSG that makes it shelf-stable. That's one of the reasons why you don't actually have to refrigerate foods like soy sauce. Some of the ingredients, plus its manufacturing process, make it more shelf stable after opening.

It brings umami flavoring to food

Our tongues taste five basic flavors: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami, which translates as "savory." For our purposes here, we focus on the savory taste that MSG brings to all kinds of dishes, from ramen to fried chicken. In these cases, the lab-made MSG is added on purpose.

However, probably unbeknownst to many, if you've ever added tomatoes or mushrooms to a recipe, like your homemade chili, then you've likely added those ingredients because of what their umami-flavoring properties add to the dish. You just bring in MSG via food instead of by salt shaker. This is something worth remembering if you'd like to experiment more with this flavor-enhancing substance but don't want to turn to manufactured MSG to do it. While these foods still have naturally-occurring monosodium glutamate in them, the bonus is if you add it via your foods, you know exactly what goes into a dish.

Finally, in Asian cooking, there is a rationale behind all of the different flavor designations, which may explain why we like some dishes over others. It boils down to basic survival as a human. For example, sweet flavors encourage carbs in the diet. A bitter flavor can warn of harmful substances, like poison. Salty foods encourage us to drink water. Sour tells us if something is spoiled. And umami consumption entices us to consume enough protein.

Cooks use it to enhance flavor

We know that MSG gives dishes a savory flavor. Because of this, many home gourmands, professional cooks, and even famous chefs, like Ming Tsai and Andrew Zimmern, add MSG to their foods. For the inexperienced MSG-using chef, finding it in spice-rack form, so to speak might be difficult. However, it is available and probably even under a name, you know. For example, the product Accent is straight MSG and nothing else.

For cooks who need to keep certain health conditions in mind, like high blood pressure, which often requires a reduction in sodium, MSG plays an important role. Human beings must consume a minimum of 1500 milligrams of sodium a day to remain healthy, but many of us have grown used to the strong flavor of salt in food and, thus, often add too much of it to our food.

But, this doesn't mean that those with health conditions that require lower levels of salt need to do away with flavor. MSG's flavor-enhancing qualities magnify the taste of salt, making the dish taste great but with less sodium. It is considered that a mix of salt and MSG allows cooks to reduce a recipe's salt level by 25%, according to a study led by Dr. Taylor C. Wallace. In this way, adding some MSG to a recipe augments the flavor of the salt that's already in the dish. This allows cooks to use less salt and still concoct more flavorful and healthier meals.

It's commonly associated with Asian food

Perhaps because MSG got its start in Asia, it has long been associated with Asian food and cooking. Unfortunately, this association also sparked a belief in the so-called "Chinese Restaurant Syndrome." This condition is said to include symptoms like dizziness and heart palpitations.

The belief that MSG is harmful to your health and, by extension, that eating Chinese food causes harm, arose in the 1960s after pediatrician Dr. Robert Ho Man Kwok contacted the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). He wanted to see if anyone else experienced adverse effects after eating Chinese food. While the responses indicated that no two symptoms were alike — more or less — in the people who reported symptoms, a belief that Asian food was harmful began to emerge. This false association, along with some shaky scientific research conducted during that time, solidified people's belief that MSG was the culprit in all of this.

Most historians and scientists now chalk this belief up to a combination of xenophobia and fear of chemicals, which also found its origins in the '60s. And to be fair, people were then and still are now eating foods, like canned foods and condiments, that are known to contain MSG and do not cause any side effects. Despite this, the MSG-is-bad-for-you debate still crops up in foodie circles, medicine, and the scientific community today.

It's actually considered safe to eat

Because of all the hype surrounding monosodium glutamate, many people opt out of consuming this seasoning. However, the fears surrounding MSG have been proven to be unfounded. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has deemed it safe to consume MSG. Not only does the FDA consider it safe for human consumption, but information on the organization's website suggests that people who take part in MSG studies don't experience consistent reactions. This is true regardless of whether they eat monosodium glutamate or if they down a placebo pill. Further, the scientific studies concerning the effects of MSG on the body have investigated both MSG from a bottle and naturally occurring MSG in food. Test subjects' reaction to the substance was consistent across the board.

Despite all this information, it's worth mentioning that the FDA requires food companies to indicate the addition of manmade monosodium glutamate on their food labels. If you're concerned about consuming too much of it, you can always check a product's label before buying it to ensure that it hasn't been added to the product.

When MSG occurs naturally in a food, no labeling is required

While ingredients like tomatoes, mushrooms, and cheese may appear on a package of frozen pizza, this doesn't mean that the food label will also include a mention of MSG. The Food and Drug Administration, or FDA, does require food manufacturers to indicate when they've added monosodium glutamate to their food IF it's truly an addition. The distinction is worth mentioning because lots of foods, like tomatoes, mushrooms, and cheese, already have natural levels of MSG within them. For foods that naturally contain MSG, no additional info on the label is required.

Given that most foods contain at least some MSG, it would be hard to label everything that contains the substance. If that weren't the case, the produce aisle in the grocery store would probably look completely different, as would the meat and cheese aisles.

This isn't to say that people don't have adverse reactions to some of these foods. Anyone can develop an intolerance to tomatoes, mushrooms, cheese, or anything else. In this case, it's critical to learn what is in the food that is causing the reaction. Maybe it's MSG. And maybe it's something else. Testing will determine the cause.

Many cured meats and fast foods have MSG

If you have yet to figure out why the popcorn at the local Cineplex Odeon movie theater tastes a zillion times better than any popcorn you've ever made at home, then you've tasted the magic of MSG in action. Due to its unique flavor-augmenting abilities, MSG has become a popular additive in foods.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, many of the foods that people claim to be addicted to, jokingly or not, contain MSG. If you read the labels on items like cured meat, pizza, ramen soup, ketchup, mustard, and more, monosodium glutamate will usually make an appearance somewhere on the food's label.

Aside from all of this, it would be difficult to go through any fast food drive-through without ending up with a little MSG in your lunch bag. Popular items, like McDonald's Chicken Nuggets, Wendy's chili, Subway's deli meat sammies, Chick-Fil-A marinated chicken offerings, Panda Express, and even some Dairy Queen items, are repositories for monosodium glutamate. We mentioned movie theater popcorn at the beginning of this section. The same idea holds true here. If some food tastes way better in a restaurant than anything you make at home, it probably has a bit of MSG in it.

Despite its name, it has no gluten

If you've ever felt unwell after consuming foods like soy sauce, you may have blamed your malaise on the monosodium glutamate in the soy sauce. But actually, soy sauce contains wheat, and your reaction may be from a wheat sensitivity instead of from a reaction to MSG. This example illustrates one common confusion about MSG and wheat gluten — that it contains gluten, but it doesn't.

It is true that once upon a time, manufacturers used gluten to make monosodium glutamate because wheat gluten naturally contains about "25% of the amino acid by weight," according to Chemical Engineering News. Still, despite this, most experts who deal with Celiac Disease consider MSG safe for those with CD to consume.

That said, the Food and Drug Administration addressed the issue of wheat gluten and MSG in a 2020 ruling. According to that ruling, any food that contains wheat gluten, even if a process like fermentation cooks the problematic elements out or at least reduces them to acceptable levels, cannot get a "gluten-free" distinction. Soy sauce, yogurt, pickles, vinegar, and cheese are among the foods that could be affected by this rule. Any products that even have a small trace of gluten must say so on the label.

MSG is a neurotransmitter

As it turns out, those memory games you used to play as a kid — the Concentration card game and Simon the electronic beeping game — may have been made all the easier if you had eaten a bowl of ramen noodle soup prior to playing. This is because glutamate — aka MSG for our purposes here – is a neurotransmitter in your brain that boosts memory function and learning.

This neurotransmitter is the brain's most abundant neurotransmitter. However, instead of taking the approach of "if a little is good, then more is always better," it's best to remember that the brain requires the amino acid in just the right amounts. Otherwise, if there is too much of it, conditions like Alzheimer's or Huntington's disease can develop. Generally speaking, too much of any nutrient to the exclusion of all others has the potential to cause issues.

However, there are some other unsubstantiated claims about glutamate that, if they are eventually proven to be true, could be quite helpful for people who suffer from conditions like nerve damage from chemotherapy or who face intellectual disorders. There is also some talk about glutamate being a possible treatment for low blood sugar, behavioral issues in children, and conditions like muscular dystrophy or epilepsy. In these cases, glutamate is said to improve the conditions, at least anecdotally.